This years’ theme for British Science Week is all about oceans: with the virtual race “Run to the Deep” and citizen science project “The Plastic Tide”, marine conservation is a hot topic for 2018. The Plastic Tide encourages the public to ‘tag’ images of the coast containing plastic litter, to create a machine learning algorithm that can automatically detect and monitor marine litter. We’ll be taking part in this project at TSP this week, and we also look back over what influence Blue Planet II might have had on the nation’s opinion of the deep blue. As TSP’s resident eco-warrior, this is a topic close to my heart. Aside from having studied biology at university – learning about the impacts of climate change on a number of ecosystems – I am a member of Manchester’s Envirolution group and am passionate about communicating environmental topics to the community.

The second series of David Attenborough’s Blue Planet soared to the top of Britain’s TV viewing charts last year, posing the question: are people more engaged with their impact on the environment than ever before?

From surfing dolphins to tool-using fish, most people will agree that seven episodes wasn’t quite enough. Among all the never-before-seen footage of marine animal behaviour, there were two running themes across the series: how technological innovations are enabling scientists and film-makers to reveal increasingly novel phenomena in marine life and, unsurprisingly, how humans are impacting ocean habitats across the globe.

British Science Week is an ideal opportunity to celebrate the leaps ocean researchers have made in uncovering the exact impacts that humans are having on marine life, from the bleaching of coral reefs due to rises in atmospheric CO2, to the effect of diminishing sea ice on walruses. Previously unheard of or misunderstood phenomena are now the subject of scientific investigation, hopefully leading to breakthrough discoveries for the mitigation of human influence on the marine environment.

Novel discoveries using cutting-edge tech

Increasingly high-tech diving equipment, as well as cameras, are enabling film crew to explore underwater for longer, with less interruption. Sometimes an animal will display a behaviour of interest only momentarily, so it’s vital that cameras are rolling for as long as possible. Diving gear that produces fewer bubbles causes less disruption to marine life, allowing undisturbed footage for longer. One instance where this was useful was in the filming of collaborative hunting between the octopus and coral trout at the Great Barrier Reef. The trout was seen to ‘point out’ prey hiding between the rocks, for the octopus to reach in and grab with its tentacles. This behaviour had never been seen before, and the team’s work has featured in newly published scientific papers.

The hidden science of climate change

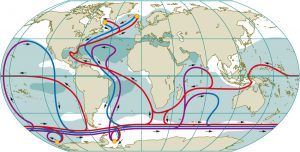

When asked to consider the meaning of global warming, most will picture a polar bear family stranded on an ice floe and, while this is important, the reality is much further-reaching and devastating. On board the vessels used for researching and filming Blue Planet, oceanographers are monitoring the sea’s behaviour. Often we think of the globe as split into the five oceans (Atlantic, Pacific, Indian, Arctic and Southern), but really they are interconnected to form the so-called ‘Global Ocean’ by the ‘global conveyor belt’. This conveyor belt transports energy (in the form of heat and movement) and matter (solids, dissolved substances and gases) and is crucial to the survival of many species.

For example, in the North Atlantic region, warm surface waters are carried by the wind-driven Gulf Stream from the tropics to the Arctic. Off the coasts of Greenland, intensely cold dry winds blow down from the ice-bound land surface, which evaporates the water, increasing the density of the ocean. This dense cold water sinks to the deep sea, forming the North Atlantic Deep Water Current. This flows southwards until it mixes with similar waters from the Antarctic, where it is then carried as Circumpolar Deep Water into the Indian and Pacific Oceans.

Worldwide ocean currents: Blue = Flow of cold, saline surface water; Red = Flow of warm surface water; Yellow circles = Convection areas

With a changing climate, the warming Arctic Ocean water is less likely to sink and feed the North Atlantic Deep Water Current, so the entire conveyor belt could be slowed or even come to a halt. This, as well as disrupting marine life, could have potentially disastrous consequences for the world’s weather and climates. With an upsurge in climate-related natural disasters seen recently, there is a pressing need to curb this trajectory.

Social media for cleaner oceans

Since the final episode of Blue Planet II aired, ocean conservation has risen to the top of conversation on social media. It is a rare occurrence to scroll down a Facebook feed without coming across a video of fish swimming through seas of plastic. A particularly powerful photo recently circulated, of a tiny seahorse clinging to a cotton bud, seems to have struck a nerve with many. Could Blue Planet, and other, similar shows be drawing the public’s attention towards the science behind global warming, animal behaviour, and what we can do in our daily lives to alleviate our impact?

social media. It is a rare occurrence to scroll down a Facebook feed without coming across a video of fish swimming through seas of plastic. A particularly powerful photo recently circulated, of a tiny seahorse clinging to a cotton bud, seems to have struck a nerve with many. Could Blue Planet, and other, similar shows be drawing the public’s attention towards the science behind global warming, animal behaviour, and what we can do in our daily lives to alleviate our impact?

Follow us on Twitter and LinkedIn to stay up-to-date with our British Science Week activities.

By Lizzie Randall, Senior Account Executive at The Scott Partnership.